Italian Men Are Not What You Think

Masculinity is far more complex and nuanced than we think it is.

There is a particular kind of look I have learned to recognize in people’s faces even before it morphs into words. It’s the concerned, forcibly compassionate look that precedes the question, “What is it like in Italy?”—a question I invariably get every time I talk about masculinity outside of my home country.

The underlying assumption is that the men-situation in Italy must be terrible. Italian men, after all, have been branded by popular culture as family-obsessed, violent, emotionally repressed, and deeply patriarchal.

From The Godfather to Goodfellas, from The Bronx Tale to The Sopranos, and Rocky to Moonstruck, masculinity has been central to the portrayal of Italian-American characters in Hollywood, and most of these characters are men who are passionate to the point of irrationality. Hyper-emotionality replaces communication.

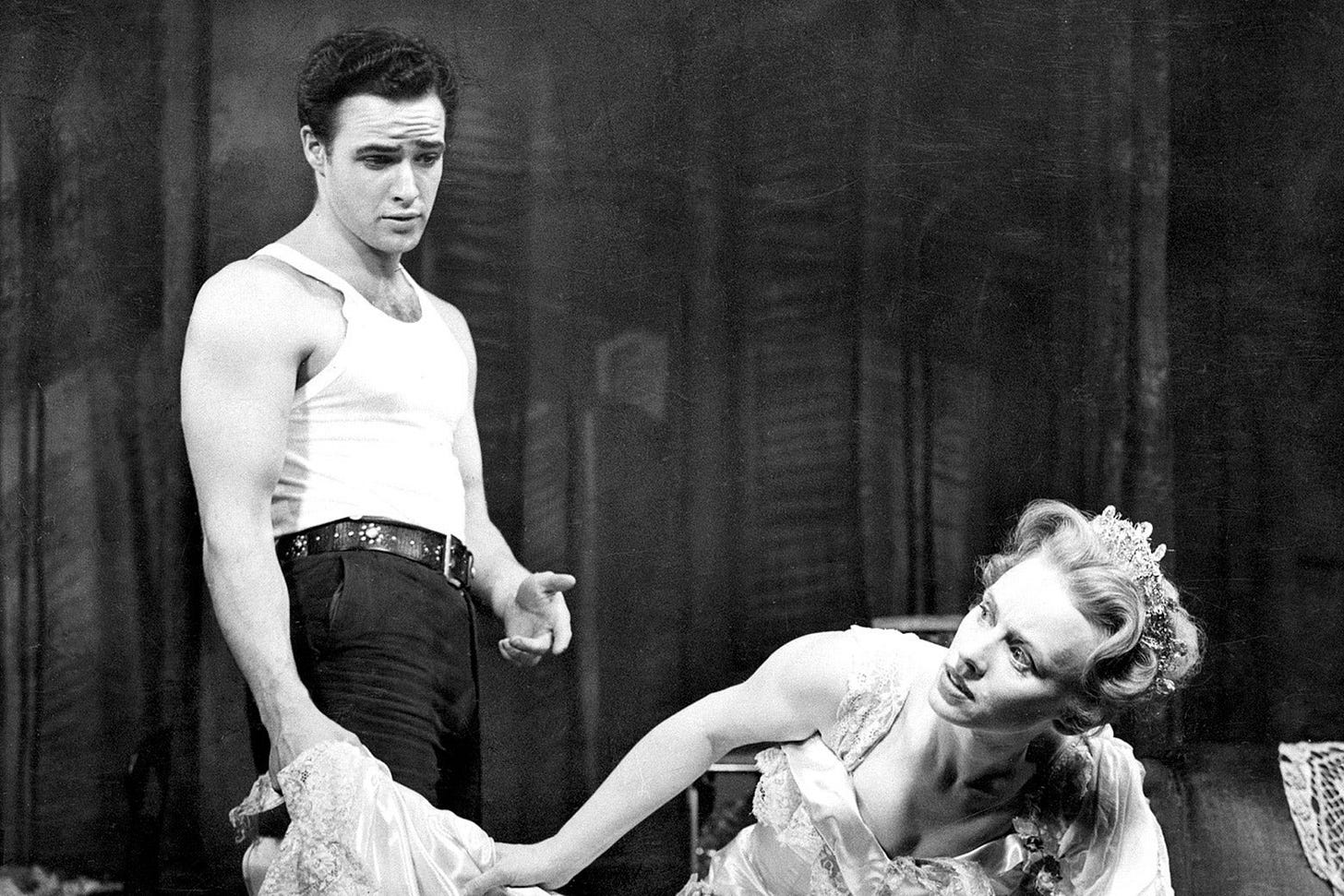

Marlon Brando in A Streetcar Named Desire (1951) isn’t Italian (his character is Polish), but his image in the white tank top yelling and lashing out has been retroactively associated with Italian-American masculinity, especially through the lens of class and domestic violence.

The white tank top—still casually called a “wife beater” in the U.S.—has become a symbol of violent, regressive masculinity. And it has been associated with Italian men. But the association wasn’t born out of Italians’ proneness to domestic violence; it was born out of racism and classism.

In mid-20th-century America, this kind of undershirt was often worn by working-class immigrant men—especially Italians—who couldn’t afford more formal clothing. Rather than being read as practical or comfortable, it was racialized and ridiculed: the garment became known as a “dago tee” or “guinea tee”, slurs that painted Italian men as uncultured, dirty, and inherently aggressive. Their bodies—hairy, loud, too emotional—were framed as excessive, too close to nature, and too far from whiteness (which is, of course, part of the reason why Italian men have been oversexualized in pop culture).

But are Italian men as emotionally repressed and violent as we think they are?

Data suggests otherwise.

In fact, Italian men are among the least violent men in the world.

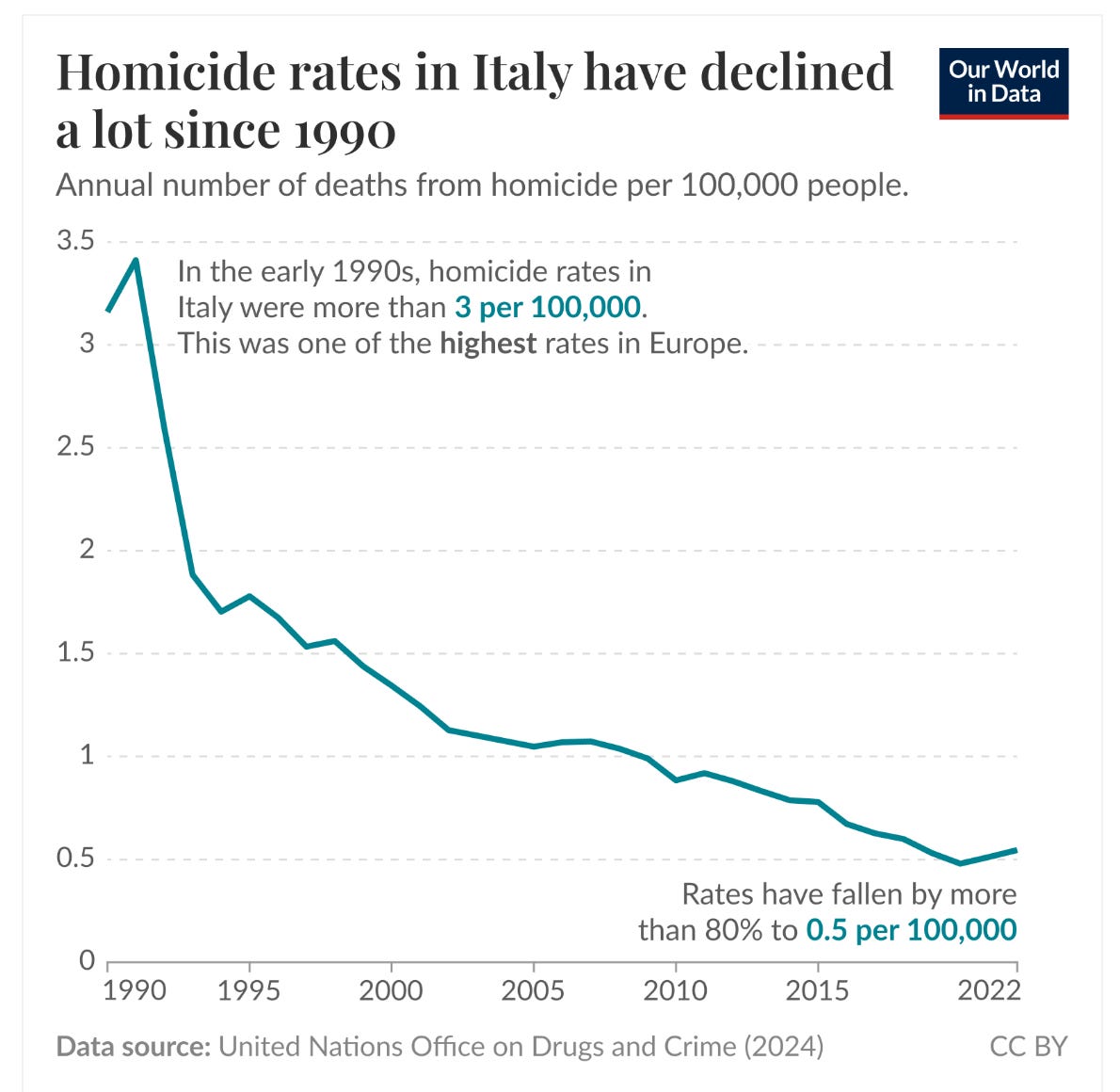

Italy has one of the lowest homicide rates in Europe—just 0.48 per 100,000 people, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

In the United States, that rate is more than fourteen times higher. Gun ownership in Italy is rare and tightly regulated; gun culture as a masculine identity marker is almost non-existent. The idea that masculinity must be linked to firepower, dominance, or “stand your ground” thinking never took root in the same way it did in the U.S., where aggression is often coded as strength and self-reliance.

Even when we narrow the lens to gender-based violence, the picture remains more complex than expected. Italy does have a serious femicide problem, but comparative data shows that other countries—such as France, Germany, and even the Netherlands—report higher rates of intimate partner killings. The numbers don’t suggest that Italian men are less sexist, but they do challenge the lazy assumption that they are more violent.

The gaze that renders Italian men “too emotional,” “too jealous,” or “too volatile” is not a neutral one—it is a colonial gaze. It emerges from a worldview that has historically positioned Northern European whiteness as the apex of civilization: self-controlled, rational, dispassionate. Under this construct, honorable masculinity is stoic and emotionally self-contained. Anything else—exuberant, embodied, relational—is seen as primitive, feminized, or dangerous. This is why Southern European men, especially working-class Italian men, were long considered “not quite white.” Their emotional expressiveness was racialized.

This colonial hierarchy of masculinity shows up even in children's media. Think of Disney movies: the only male characters who are emotionally expressive are depicted either as monstrous (the Beast), outcasts (the Hunchback of Notre Dame), or… “exotic” (Aladdin, Miguel in Coco, O’Malley in The Aristocats).

Southern European and Latino men, their food, their families, their bodies, their accents—all became part of a performance coded as uncivilized masculinity. But here’s the paradox: the same cultures that celebrated emotional repression as a masculine virtue also built political and domestic systems with higher rates of interpersonal and state-sanctioned violence. The myth of the composed, rational man—central to whiteness—conceals a deep inability to metabolize emotion, especially vulnerability. And when feelings have nowhere to go, they often erupt as violence. In this light, the emotional availability and embodied chaos of Italian masculinity—often used to justify its inferiority—might be exactly what has kept it from fully succumbing to the violence that haunts more “civilized” masculine ideals.

When I moved to the United States in my twenties, I experienced something very confusing in terms of the relationship between men and women: on the one hand, I was finally taken seriously on the job. In Italy, as a young woman, it had been impossible (so much that to forge my career, I moved to the other side of the world). Italy, in fact, has a tragic problem with the underemployment of women.

On the other hand, I was shocked to see that parties were often way more gender-segregated than in Italy. Men tended to stick with men; they hung around the BBQ and drank beer. Women drank wine and ate cheese on the other side of the garden, or in the other room.

Outside of a professional setting, I realized that young men talked to women if they wanted to date them. I found myself in a couple of very awkward situations because I thought I was striking up a new friendship, while the other person assumed we were flirting. The simple act of talking across gender lines carried romantic expectations I hadn’t grown up with. Men and women appeared to have way more conservative gender expectations than I had experienced in Italy, the whole culture of prom being a monument to traditional gender norms.

This paradox stayed with me. The U.S.—a country that has so confidently positioned itself as more modern, more equal—seemed to have normalized a deep emotional distance between the sexes. Yes, women were in the workplace, and in many ways, empowered professionally. But interpersonal dynamics were governed by a surprisingly rigid code. Beneath the surface of a liberal society, I encountered an emotional landscape more cautious, more transactional, and, in some ways, more lonely than the one I had grown up in.

In Italy, gender dynamics are full of contradiction, no doubt. But in everyday life, men and women interact constantly, informally, and without the same degree of social scripting. There is messiness, but there is also relational fluency—a kind of emotional openness that doesn’t require a romantic premise to exist. And that, I’ve come to believe, matters. It might even be protective.

Because when masculinity is defined not just by stoicism but by emotional avoidance—when boys are taught that vulnerability is weakness and connection is dangerous—what emerges is not neutrality. It’s numbness. And numbness, left unchecked, becomes cruelty.

As I travel the world talking about masculinity, I have started to notice that many men from countries that we have associated with “macho” culture are actually way more open to reflecting upon the construction of their masculinity. That, in general, they are more capable of introspection and more aware of their inner life. They are also confident enough to wear their heart on their sleeve, without feeling the need to pretend they have no emotions.

In Hollywood, even the extreme violence of American men is never portrayed as “passionate”; it is always presented as the only solution to an extreme situation that couldn’t be solved otherwise.

Hollywood has exported a mythology in which American masculinity is pragmatic, rational, and redemptive—even when violent. The cowboy, the soldier, the action hero—they all kill, but they do so cleanly, stoically, with purpose. In these stories, violence is not impulsive or emotional—it’s necessary. This narrative not only masks the emotional repression that underlies much real-world violence, it also delegitimizes other, more expressive ways of being male. When anger is acceptable but grief is not, we confuse hardness for strength, and weakness for feeling.

What we call “progress” is often just a reflection of the metrics we’ve chosen to care about. Workplace participation matters. Legal rights matter. But if we ignore the emotional and relational cultures that shape how men relate to themselves and others—how they metabolize powerlessness, how they hold sadness, how they process shame—we miss the deeper currents driving both connection and violence.

Look, I’m not interested in flipping the script to say that Italian men are “better.” That would be just another myth. What I’m advocating for is something far less cinematic and far more urgent: a culture where men, regardless of where they’re from, are allowed—encouraged—to be emotionally expressive, relationally fluent, and self-aware. A culture where masculinity is not measured by control, but by connection.

Maybe there is a reason why Boys of the Future was born in Italy. I sensed a unique space here—a space where men are emotionally entangled in daily life, where contradictions live side by side, and where they are allowed to be more in tune with their inner life. Traveling the world to talk about masculinity gave me hope that Italian men could be the pioneers of the kind of new masculinity we so desperately need. Because here, under the noise, the contradictions, the tomato sauce stains—there’s a kind of emotional vocabulary that, if we listen closely, might be just what we need to rewrite the script.

If you are raising boys and would like them to be more emotionally expressive and self-aware, check out my new book Stellar Stories for Boys of the Future, the first collection of original tales designed to offer all children a healthier understanding of what masculinity can be. The book is also out in Italian, Spanish, German, Danish, Brazilian Portuguese, and it will be published in Croatian, Catalan and Polish by the end of the year.

Have you watched my TEDx talk, titled How Fairytales Teach Boys to Hide their Emotions?

On Wednesday, July 16th at 7pm CEST I will do an Instagram LIVE presentation of Stellar Stories for Boys of the Future with German journalist and book author Shila Behjat. If you are interested, save the date and join us!