Decolonizing Fairytales: My Queer Journey (Beyond Wokeism)

What’s missing from kids’ stories—and why it matters

I am a queer woman, and I grew up in a small town in Southern Italy.

I was always an avid reader, but I never stumbled on someone like me in any of the books my mother bought me or in the ones I borrowed from my school library. I never saw someone like me in the cartoons I watched with my sister. As a result, it took me 23 years to figure out two things:

a) that lesbians existed;

b) that I was one.

In my early twenties, as I started to realize who I was, I also started to see more clearly where I was coming from. At about the same time, I discovered not only that I was a lesbian but also that I came from a place that had been colonized (Northern Italy colonized the South during the country's Unification between 1861 and 1870). The legacy of colonization had already made a huge difference in my life.

My hometown was 2 miles away from a huge dump for so-called ‘non-dangerous toxic waste’ and 12 miles away from an enormous steel factory - both the dump and the steel factory are the biggest in Europe in each category. My grandfather died of leukemia, like too many other people in the area (including children—dioxin is found in breast milk in Taranto).

This was a truly eye-opening time for me. So many aspects of my life that I had considered unworthy of attention started to seem important… crucial even. My identity was being questioned, as was the way the entire world worked!

I had a distinct feeling that so much had been kept from me, and that feeling drove me mad.

Because I was never presented with a queer character, I spent my entire adolescence and early adulthood feeling like there was something wrong with me.

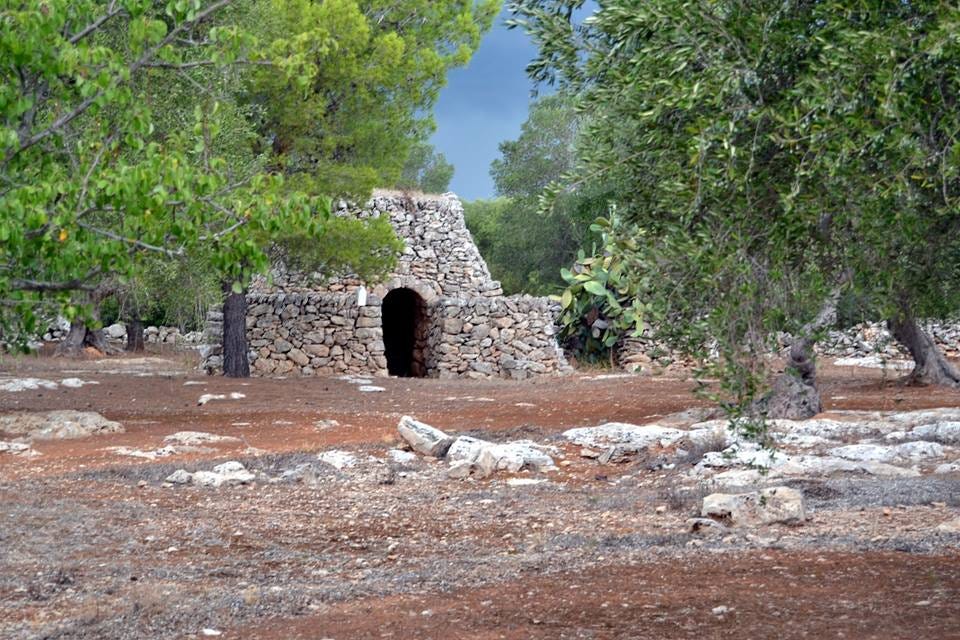

Because the places I found in books always looked different from the ones where I came from, I grew up thinking that we were not worthy of being in books. As embarrassing as it is to admit, I grew up thinking there was a reason why the dump and the steel factory were placed close to my town: what did we have that was worthy of being preserved after all? Not grass, not apple orchards, not cows, no castles… just old olive trees, barbary figs, sand, and unfinished buildings.

The Power of Missing Stories

All of a sudden, the stories, the characters that had seemed so varied, so different from one another, suddenly started to appear irritatingly homogenous. Why was I reading yet another book about a man who was braving the wilderness and finding a way to tame other men, other creatures, or an entire civilization to prove his value?

Why was I reading yet another story about a good-hearted, invariably beautiful princess unable to defend herself from the meanness of an ugly stepmother/stepsisters/husband/passing-by witch?

Why was I reading yet another story that was inventive enough to describe in vivid detail fantastic animals but somehow could not muster up the courage to get rid of a rigid class system? What else was missing from the stories I had been fed?

And what were the effects on society, and kids in particular, of silencing all those other stories?

I knew what the effects of those voids were on me.

Children’s literature is imbued with colonialism not just because of what is in the stories but also because of all that is missing. The missing characters, places, and stories teach kids what deserves to be in books and what doesn’t.

Children’s stories and their role in shaping the world

Children’s literature is inherently political. The first stories children consume inform their perception of what the world is and shape their understanding of what they can expect from it, of what the world can expect from them.

Children’s expectations about the world become the world.

Historically, children’s stories have been instrumental in building the moral foundation of our society.

We are all very familiar with the moral of some of the most famous children’s stories of our tradition. Pinocchio? Lies get you in trouble. Little Red Riding Hood? Don’t trust strangers. Three Little Pigs? Hard work is important!

Over time, children’s entertainment has evolved significantly, and the moral of the stories our kids consume can’t be nailed so simply anymore. Let’s think of Frozen, for example, a modern classic seen by tens of millions of children around the world. The moral of the movie is complex and modern: the story teaches kids about family love but also about the importance of embracing one’s true self, it even goes as far as questioning the importance of romantic love - unheard of for a story starring two princesses!

Children absorb stories differently

The “moral of the story,” though, does not comprise the entirety of what children learn when they read or watch something. In fact, the “message,” the thing that makes us - the grown-ups - feel good and even tear up about what we are showing our kids… in most cases, remains of no interest to the kids. Kids tend to focus on much, much smaller details and experience stories in ways that are fundamentally different from ours.

If we want to make sure that our stories do not reinforce values that are fundamental to colonialism, such as economic exploitation, ethnocentrism, racism, paternalism, etc., we must understand what happens in children’s imagination when they are exposed to a story.

The Frozen Example

Despite the modernity of Elsa’s journey of self-discovery, there isn’t a single moment where the fact that she lives in a castle is put under scrutiny. Yet, we know very well that the social structures that allowed some of us to live in castles were based on economic exploitation.

When girls buy Elsa’s toys to feel more like her, they are not just buying her desire to live an authentic life. In fact, they are mainly buying the colonial ideal of beauty and success: her blonde, thin body, her castle, and her beautiful gown.

Although this character's inner journey may have changed, the circumstances, details, and way the character is presented to children have remained the same.

Real-world examples: the girl who stopped eating chocolate

One of my closest friends is from Sri Lanka. She and her husband have an incredibly smart daughter. One day, she got home and announced she wasn’t going to eat her favorite—chocolate ice cream—anymore. When my friend asked her why, she said she wanted to be like Elsa… and thought chocolate ice cream would make her skin darker.

Children explore stories in ways that are different from ours, and their unique perspective has the power to reveal agendas we may not even be aware of, an imprinting we received and forgot about, one that we may be uncomfortable acknowledging.

By making a princess living in a castle the character worthy of such an important spiritual journey, we are de facto replicating the colonial idea that whiteness and wealth make people not only more powerful but also morally superior to other human beings.

This idea is rooted in us way deeper than most of us are willing to admit.

Is this ‘wokeism’?

At this point, you may be ready to label the approach I am describing as ‘wokeism’. After all, adding marginalized people to TV shows and (to a lesser extent) children’s books—even changing published works by deceased authors—seems to have been a must over the past few years. However, what we have mostly seen so far is the publishers’ obsession with using the ‘right’ words: the need to be immune to criticism trumped the willingness to open an honest conversation about these important issues.

Decolonized stories will allow our conversations to go deeper. If all our effort do is sanitize our communication with the hope that we don’t find ourselves in any uncomfortable places, we are simply failing to produce culture that matters. We are fabricating our own irrelevance (hello 2025!), and by doing so, we are damaging our democracies.

The journey to decolonize children’s stories is a political and a spiritual one.

It starts with our willingness to examine ourselves and do the work necessary to free ourselves from the need to dominate others. It is not a matter of instilling guilt in younger generations—take it from a Catholic-raised Italian—nothing good ever came from instilling guilt in people.

It’s not the topic we choose that makes a story ‘decolonized.’

It’s the kind of human we want to be after reading it.

I never write to teach children about something. I write to learn with them. I ask myself difficult questions and share the process of seeking answers with my little readers and their families.

I do my best to sit with my little readers before the complexity of the world, to hold their hand when it gets a bit harder or even painful. My job, the way I see it, is to be there, to make it possible for them to see, to wonder about the nature of life, and to imagine what their role will be in creating a just, peaceful world.

LGBTQ+ characters in children’s stories

Often, children’s stories that include LGBTQ+ characters are considered ideological. But I don’t get what that means. LGTBQ+ people exist, and they have always existed throughout the world in every single country and culture.

Censoring the presence of LGBTQ+ people in children’s stories because they don’t match our own personal preference of what the world is supposed to be in our imagination… well, that sounds extremely ideological to me. It’s just an ideology we are more used to, but it’s still ideology.

I try to find ways to show children the world in all of its glorious diversity: eliminating the presence of entire categories of *existing* people simply because they don’t serve the kind of narration we are comfortable with is a profound betrayal of our mission as children’s book authors.

The aspiration to a ‘perfect’ life

The idea that we can or should aspire to a world that doesn’t trouble us, that never puts us on the spot, and the idea that we should dream of a life that is tailored to our dreams and capabilities… is at the core of most children’s narratives. And it is a colonial one.

Colonial powers justified all sorts of violence against humans and against nature by buying into the delusion that by bending nature, coercing other human beings to comply with their desires, and appropriating as many resources as they could, they could bring their vision to life. Then, they sold us the idea that bringing our vision to life, no matter the cost, is what makes us heroes.

A Journey of Radical Imagination

When I started working on Stellar Stories for Boys of the Future, I wondered if I was reinforcing a binary concept of gender. Many heterosexual, cis-gender editors tried to convince me to adopt a “gender-neutral” approach to the book and get rid of the “boys” part. However, the book was born out of a profound investigation of societal expectations towards boys and men. It was born out of the realization that we have not reflected nearly enough on the narratives we are offering boys, so why was I supposed to bury that work under a gender-neutral, hip label?

As a queer girl, I grew up in an unusual limbo: I was a girl, but I never saw myself in princesses. I always saw myself as a prince and fighter. I wanted to be Tigerman, McGiver, Batman. One of the first stories I wrote was about saving from kidnapping a girl I had a crush on in middle school.

This peculiar experience gave me a unique perspective on gender, and I thought I could offer to my readers my own lived experience as a bridge between two worlds that often seem impossible to reconcile.

After all, gender has been everything but neutral to me. So why should I pretend otherwise?

Stellar Stories for Boys of the Future is the most ambitious book I have ever written because it is my conscious attempt to create a fun, adventurous, heart-warming collection of stories designed to inspire children to live as they are outside the boundaries of colonial imagination.

The characters in the stories give back their castles to the people; their goal isn’t to become as strong as possible but to learn how to use their strength to free themselves and others. They are not afraid to break free from tradition if that means gaining a freedom that their ancestors never allowed themselves to experience.

They don’t need to be heroes because they are part of a community and experience how “no one can swim alone through the darkest darkness.”

These characters (sharks, pirates, ogres, frogs…) live life with an explorer mindset. They don’t travel the world not for the sake of success or self-realization but because of a much more powerful and enchanting force: curiosity.

Within the colonial mindset, curiosity without conquest is childish. Exploration without appropriation is a worthless exercise for people who “don’t have what it takes.”

A quote from Lao Tsu opens one of my favorite books of all time: “Da cosa nasce cosa,” by the Italian master of design Bruno Munari.

Here it is:

"To give birth, to nourish,

To bring forth without taking possession, To produce without appropriation,

To create without controlling-

That is the hidden virtue."

What are the hidden virtues that are woven into the stories we tell our children?

The path that leads us away from domination and toward peace is certainly a long one, and some may say that the creation of a better world is nothing more than utopia. But why write for children at all if we are not interested in the longest possible shot, in the widest possible horizon?

I am so excited for the book. I’m currently reading Goodnight Stories for Rebel Girls and my 6yo said after we finished reading about Amelia Earhart “I heard there are not many women astronauts, I could do that.”

Having stories that allow our children to say: “I noticed ____ …. so I wonder ____….” I love learning besides my children, to see the world from an investigator sociologist, observing and questioning. Thanks for continuing to write, just pre-ordered it.