"Adolescence": the fight for boys' souls

The hit Netflix show confronts us all with a question: what can we do now?

Adolescence made millions of people realize that there is a battle going on, one that we know almost nothing about because - until now - we have mainly chosen to ignore it. It’s the battle for the souls of boys. Arguably, the most consequential battle of our time.

As viewers of this British TV series, we leave the experience with a burning question that has nothing to do with the show and everything to do with our lives: “what can we do now?”

The answer is not easy, but there is hope.

The manosphere is here

The name “manosphere” evokes dark corners of the internet where outcast boys and men are sold a deep-seated hatred for women, ill-conceived dating advice, workout routines, “self-help” online courses, and… supplements, lots of them.

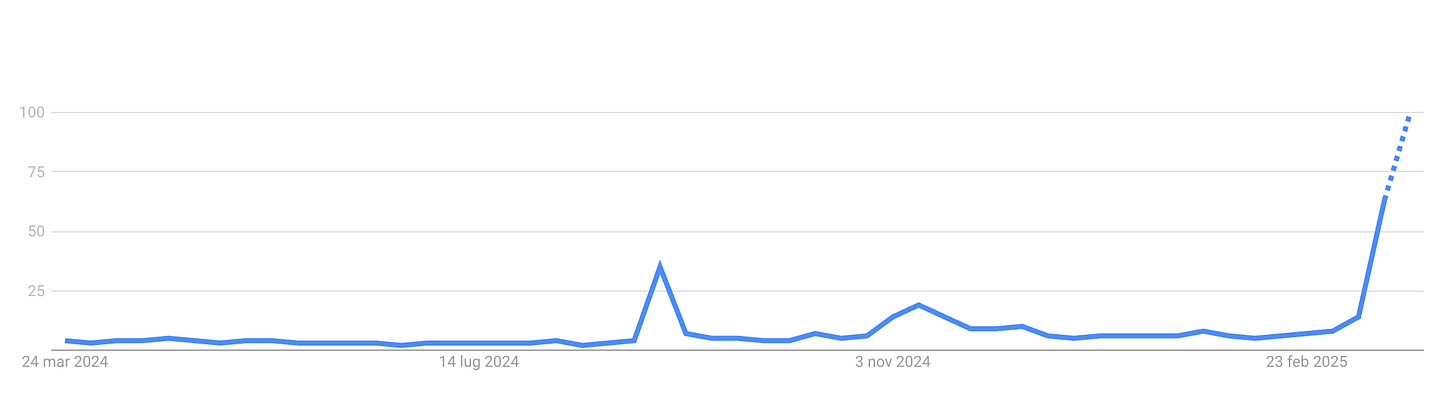

Until a few months ago, the term manosphere was rare in the public discourse. It was easy to associate it with a weird subculture that did not affect us or anyone we knew.

Then came the US Presidential election.

Donald Trump, with the help of his teenage son Barron, specifically targeted some of the biggest influencers in the manosphere: He appeared on Logan Paul’s podcast and Joe Rogan’s, and made a deliberate effort to reach what he called a “key demographic” in some of the most contested states: disenfranchised young male voters, white, Latino, and black—about 10% of voters.

Trump’s bid paid off, and - overnight - his victory made clear that what we had considered a “weird subculture” was actually the mainstream. We just hadn’t noticed.

Trump’s election felt different this time precisely because of this: during Trump 1, we could at least tell ourselves that sure, Trump had been smarter strategically, but he hadn’t won the popular vote, he hadn’t won the culture over. We felt we were still the majority, that we - not them - were embodying the zeitgeist.

This time, uh uh.

This election left many in a state of stupor. We are experiencing a mix of numbness, surprise, and shock. It’s understandable. We don’t even know if we can trust ourselves since the world seems suddenly quite different from what we had imagined.

In this sense, the story brought to our screens by Jack Thorne for Netflix perfectly captures the feelings that many of us have been experiencing since last November.

Adolescence is making waves not just because it is an unbelievably well-written and directed show with outstanding actors but because it’s the first series showing us how widespread this culture is, how it’s already in our homes, in our kids’ bedrooms, how it is already shaping our life across cities and countries.

Adolescence is painful to watch because it forces us to confront the consequences of our collective choice to ignore men’s struggles and boys’ need for encouragement and guidance.

Maybe, we’re all responsible for this

Jamie’s dad is probably the most heartbreaking character in the entire show. Raised by a violent father, he swore never to repeat the cycle. He tries very hard to be a good man, an affectionate husband, and a responsible father. And, perhaps unsurprisingly, he has issues with emotional regulation. He accepts to go to therapy with his wife, but - like so many other men - it appears like he would not go by himself.

But surviving a childhood with violent beatings by a parent figure is no joke, and it is a feat that can hardly be taken on without counseling.

If money is tight, a man is more likely to go to therapy if he can justify it with the goal of keeping the family together (hence couples therapy), but working on oneself still seems like a waste of time and money. Of course, the work that most men are avoiding is precisely the kind of work that’s most needed.

Jamie’s father breaks our hearts not because he is a perfect father but because he is real.

He is the kind of man we haven’t seen enough on our screens: one who makes mistakes but keeps trying. He is lost. He wants to be better than his father, and he feels inadequate; he’s afraid he’s not enough for the challenge his family is going through. He feels like there is something that he is missing, but he doesn’t know how to grasp it. At times, the pain feels unbearable.

Jamie's mother doesn’t need him to be perfect; she gives him space to be himself and tries to find ways to process all that is happening. She appears to be more aware of her husband, but being at different levels of self-awareness doesn’t tear them apart. They are a family and never cease to be one. Together, they try to make sense of their son’s senseless violence.

We have become so used to dividing the world neatly into abusers and victims, in good and bad, in oppressed and oppressors, that we have forgotten that life is more complicated than that.

Jamie’s mom and dad haven’t forgotten, though.

Far away from the internet and deeply rooted in real life, Jamie’s parents don’t read the circumstances of their lives through the lens of social media culture wars. They are capable of questioning themselves, and, at the same time, understand that the forces at play are bigger and that they can’t possibly control everything. “Maybe we are all responsible for this,” says Jamie’s dad, and he is right.

It is time to come to terms with the fact that male violence is a collective responsibility. As long as we keep on considering it the product of the individual circumstances of the life of a single boy or man, we won’t be able to address it effectively. As long as we consider it inevitable because ‘boys will be boys,’ we won’t be able to do anything about it.

Anti-misogyny classes are not the solution

Jamie does not respect himself. Like many incels, Jamie thinks he is ugly; he thinks he is a loser. The influencers of the manosphere need their followers to feel like that because it is their self-hatred that pushes them to consume their content and buy their products (subscriptions, supplements, online courses, etc).

Feminism questioned the role of women and, consequently, men's role in the world. It caused a shift that, understandably, made many men feel insecure. To quote Billie Eilish, it made many boys and men ask themselves, “What was I made for?”

In the oversimplification and radicalization of social media, masculinity became “toxic,” and “hetero-cis-white-man” became a formula used to quickly attribute responsibility for all that is bad and hopeless in the world to a single category of people.

Many young men did not approach the manosphere because they hated women. They did so because they felt lonely, unlovable, disconnected, worthless. The isolation and mental health emergency created by social media, paired with the (attempted but not quite achieved) reshuffle of the world order, created a perfect storm.

The influencers of masculinity started monetizing boys’ and men’s discomfort by offering them an array of “solutions” to that feeling of inadequacy. They stoked it; they blamed women for it. They told boys that if only they became tougher, stronger, that if only they bought the secrets they were holding they could find through them the respect and sense of belonging they are unable to find in themselves, in their families, in society.

Unless we teach boys to respect themselves, though, we won’t be able to teach them to respect women. The manosphere is filling a giant void that we must fill with connection, love, and purpose. This is why anti-misogyny classes are not the solution. They treat the symptom, not the cause of the illness.

The foundations of the manosphere may not strictly centre on misogyny, as is popularly imagined, but in young men’s search for connection, truth, control and community at a time when all are increasingly ill-defined.

The draw of the ‘manosphere’: understanding Andrew Tate’s appeal to lost men, The Conversation

Telling boys not to hate women isn’t the solution. It is actually a way to reinforce the idea that there is something fundamentally wrong with masculinity, something that we must fix. But there isn’t. What’s toxic is the stereotypes we have attached to masculinity, the idea that men can’t have feelings, the homophobia, and the brutality of a system that makes the amount of money you make the ultimate measure of your value as a human being.

Misogyny isn’t men hating women; it is men hating in women what they have been taught to hate about themselves.

Deep down, we know what must be fixed

It’s Jamie the first to bring up the moment when he feels his father is ashamed of him during a soccer game. He says that his father “can’t look at him.” And later in the show, his father talks about the same moment. He, too, knows that what happened there wasn’t right.

Shame is at the core of what is wrong with masculinity. Our current interpretation of masculinity revolves around it. Boys stop dancing; they stop cuddling; they stop crying; they stop asking for help; they are afraid to walk or move their hands in the wrong way; they lower their voices, and they stop singing because they are afraid of ridicule.

We talked so much about the awful damage that homophobia inflicts on gay and trans kids, but nobody talks about the damage it inflicts on heterosexual cis men. It’s so bad that men on X who talk about their feelings use the hashtag #nohomo. Like… really?

Adolescence is an abrupt wake-up call.

The election of people who wear callousness and brute violence as badges of honor and the rise of cynicism are not good signs, we all know that. The crisis of masculinity has created a giant dark hole, and - when you look at international politics - it’s becoming clear that we are all on the brink of being sucked in.

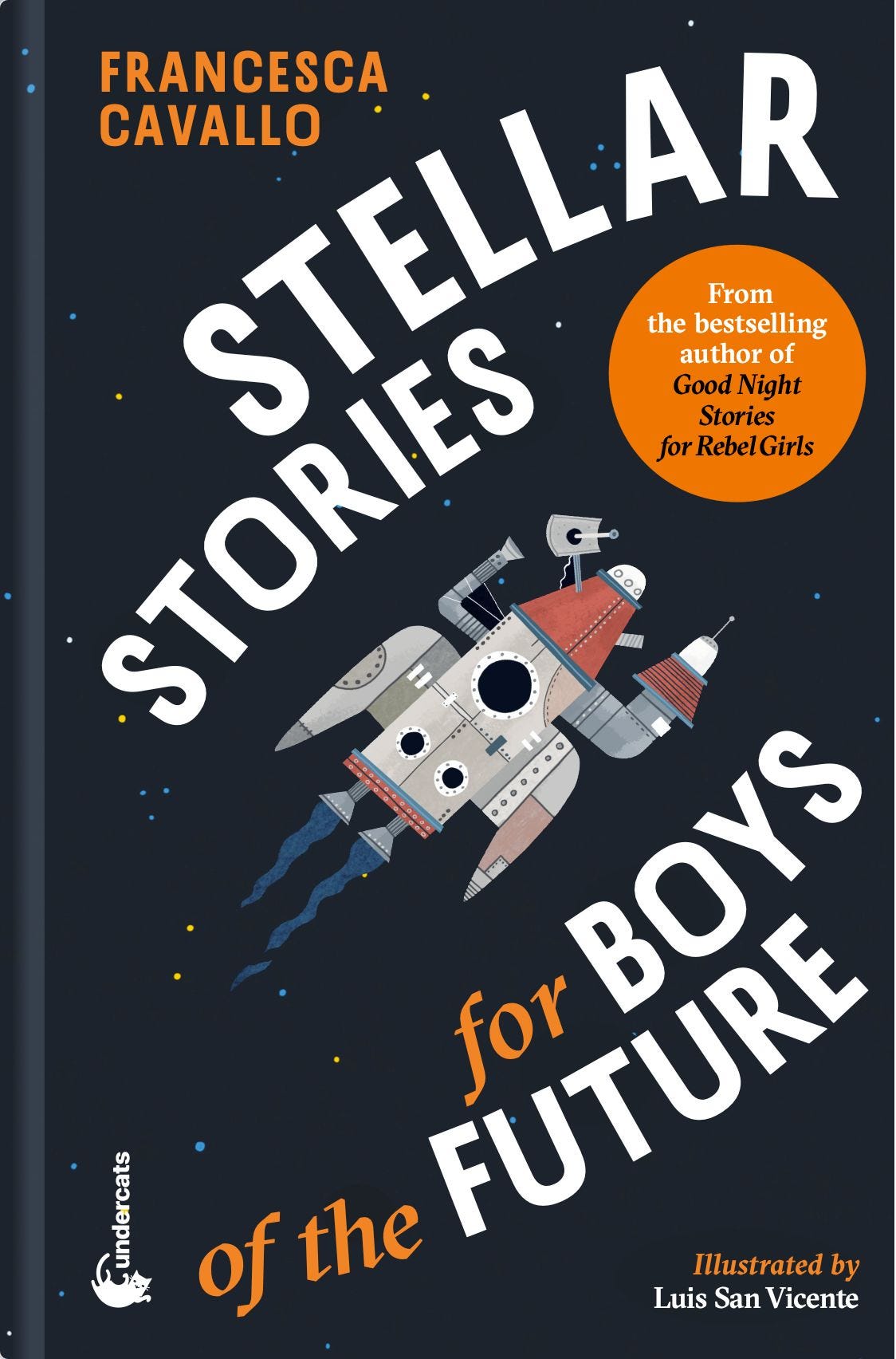

Passing judgment, though, is not going to fix anything. We are called to exercise radical imagination and start building a different world. That’s why I imagined 12 new planets in my new book, Stellar Stories for Boys of the Future, the first anthology of original tales created to offer all children a healthier, more wholesome idea of masculinity and of all the beautiful ways in which we can learn to be and to dream together.

It came out last week, and Publishing Perspectives wrote a beautiful piece about it.

It is an attempt at holding space, making masculinity wider, and offering kids more room to explore it. I hope you enjoy it.

Each crisis is an opportunity

Here’s to cultivating hope. Each crisis is an opportunity. The crisis we are going through is offering us the crucial opportunity to rewire the way we decide what’s worthy and what isn’t. An opportunity to seek meaning over the mindless accumulation of wealth, to value service more than power.

It’s not just boys who need this. It’s all of us. And I believe that, deep down, we know it.

"Misogyny isn’t men hating women; it is men hating in women what they have been taught to hate about themselves." -- Succinct and painfully accurate. I haven't watched this series yet but hope to soon as I've heard a lot about it. As always, thank you for what you do!

This is such a powerful and moving piece. I really appreciate how you name the emotional isolation and shame at the heart of so much of what’s going wrong with masculinity today—especially for boys and young men trying to find their place in a rapidly shifting world.

Reading this, I kept thinking about the concept of patriarchal masculinity, which scholars like Bell Hooks and Riane Eisler have explored deeply. The traits that are hurting boys—emotional suppression, homophobia, the drive for domination and control—aren’t inherent to men. They’re a product of patriarchal systems that have long dictated what’s “acceptable” for boys to feel and express.

This also echoes ideas from Gabor Maté, particularly in The Myth of Normal, where he shows how trauma, disconnection, and emotional repression manifest in everything from addiction to chronic illness. What we call “toxic masculinity” often begins as unhealed pain in boys who never had safe spaces to feel or be vulnerable.

A few other books came to mind as I read: “Nurturing Our Humanity” by Riane Eisler and Douglas Fry, which explores how societies rooted in domination (rather than partnership) shape everything from our gender norms to our politics; and

“The Wheel of Change” by Eisler, which offers a hopeful framework for rewiring systems—from education to economics—to prioritize care, connection, and mutual respect.

Your call for radical imagination and more expansive visions of masculinity is right on target. And yes—it’s not just boys who need this shift. We all do. Thank you for creating stories that move us in this direction. I’ll be picking up Stellar Stories for Boys of the Future—sounds like something I want to read with my kids.